Working Harder, Paying Less: Wage Suppression in Greece

The state of the labor market in Greece exemplifies the socioeconomic damage caused by austerity.[i] More than 15 years into a recession that has proven both deep and enduring, signs of a full recovery remain absent. Declining living standards, an increased tax burden, and the deterioration of public infrastructure and services have all contributed to ongoing economic stagnation and persistent structural vulnerabilities (Missos et al. 2024a).

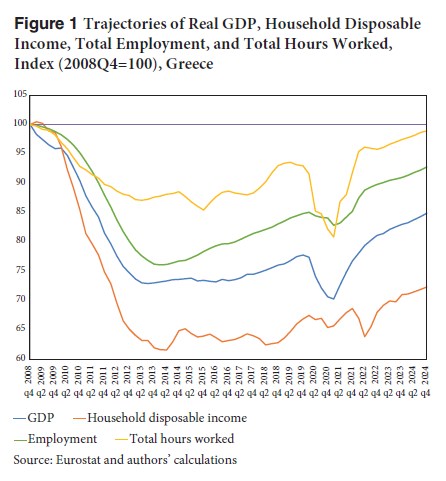

As shown in Figure 1, since the beginning of the 2008–9 financial crisis, the GDP has contracted by 27 percent and has yet to return to its pre-crisis level. Total household disposable income has fallen even further, by 35 percentage points, highlighting the population’s intense financial strain and the growing divergence between income and total output.

However, although the economy has adjusted to a lower level of operability, total employment is nearing full recovery, and the total number of hours worked has already returned to pre-crisis levels. This current phase of job creation, characterized by positions that contribute significantly less to domestic demand than in the past, has been described as a period of “growthless employment.” This reflects a substantial downward shift, both in quantitative and qualitative terms (Vaitsos and Missos 2025). The economy appears to be generating new, low-paying jobs, insufficient to sustain the previous levels of domestic spending needed to support a full recovery.

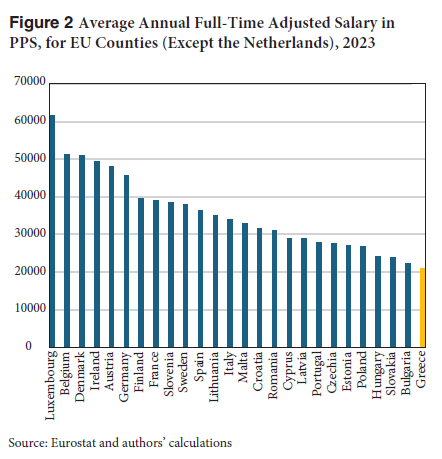

The average annual full-time adjusted salary per employee (AFTS) reflects the income level considered adequate for maintaining a decent standard of living within EU27.[ii] The estimate is based on the average gross salary earned from full-time employment over the course of a year. According to the latest data released by Eurostat for the year 2023 (see Figure 2), Greece ranks last among all EU countries in terms of AFTS when measured in Purchasing Power Standards (PPS). The PPS is increasingly employed in cross-national analyses to account for economic disparities within the EU (Missos 2024). As defined by Eurostat (2008, 49), PPS functions as a currency conversion tool that adjusts for differences in price levels across countries. It allows for expenditures, originally expressed in national currencies, to be translated into a common unit of value. While PPS facilitates meaningful comparisons between countries, it is not intended for tracking changes over time within a single country.

This development is not new for the level of payments in Greece. Since 2010, Greece has experienced a massive deterioration in labor compensation and disposable income (Missos et al. 2024a). Austerity policies have continued unabated and their effects have become permanent, shaping the institutional setup of industrial relations and the framework of the labor market. The economic adjustment programs implemented in Greece have imposed a series of structural reforms. Among others, reforms were promoted, making wages much more responsive to GDP adjustments and market fluctuations.

Increasing labor market flexibility was one of the main pillars underpinning the adjustment programs. Reducing rigidities and dismantling labor protection legislation in order to liberalize the labor market were considered critical steps toward employment recovery. Additionally, internal devaluation was another key component in the overall policy framework. In the absence of external exchange rate adjustment mechanisms, the burden of restoring price competitiveness fell largely on labor costs (Pierros 2021).

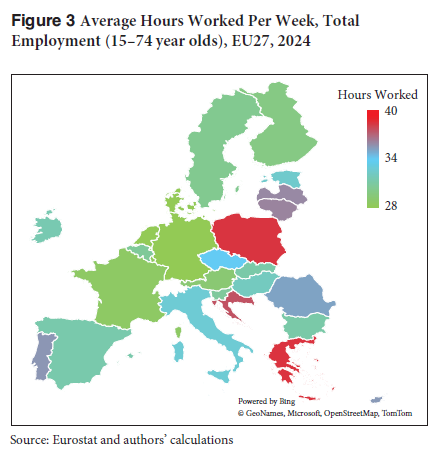

The repercussions of labor market reforms did not end with the completion of the third and final economic adjustment program in 2018. On the contrary, labor flexibility in Greece has become a structural feature of its industrial relations, being embedded in the legal framework shaping employer-employee relations. A clear example of the enduring nature of this approach is the introduction of new measures under Law 5053/2023, which allow for a six-day working week in specific sectors, including certain businesses and manufacturing.[iii] As a result, the working day would likely extend beyond conventional limits.

Be that as it may, Figure 3 shows that, by 2024, the average employee in Greece—whether salaried or self-employed—is estimated to have worked for 38.5 hours per week, the highest among all EU27 countries. Poland ranks closely behind (38.4). In Greece, however, work intensity appears to have increased, with the average working day extending beyond standard hours. This trend appears to be driven by three main factors. First, with labor protection legislation in decline, employees face increasing difficulty negotiating reduced working hours for standard employment. Second, in response to rising living costs (Missos et al. 2024b), many workers seek to work overtime in order to support their households. Third, most newly created jobs are relatively low-paid, and the EU27 average number of hours worked is insufficient to cover basic living expenses.

Be that as it may, Figure 3 shows that, by 2024, the average employee in Greece—whether salaried or self-employed—is estimated to have worked for 38.5 hours per week, the highest among all EU27 countries. Poland ranks closely behind (38.4). In Greece, however, work intensity appears to have increased, with the average working day extending beyond standard hours. This trend appears to be driven by three main factors. First, with labor protection legislation in decline, employees face increasing difficulty negotiating reduced working hours for standard employment. Second, in response to rising living costs (Missos et al. 2024b), many workers seek to work overtime in order to support their households. Third, most newly created jobs are relatively low-paid, and the EU27 average number of hours worked is insufficient to cover basic living expenses.

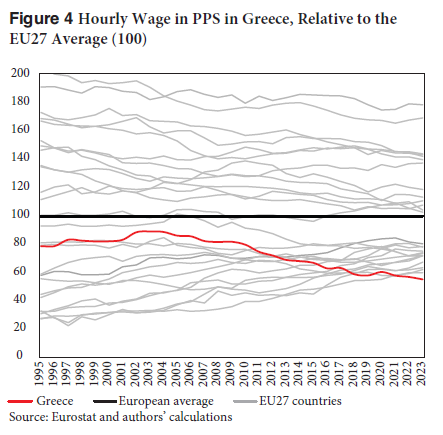

The latter plays a significant role in shaping the hourly wage measured in PPS. Figure 4 illustrates the hourly wage across all EU27 countries relative to the European average (set at 100). Between 1995 and 2004, the average wage in Greece displayed a trend of convergence toward the EU average. However, from that point onward, the hourly wage in PPS terms gradually diverged, eventually becoming the lowest in the EU27. Notably, the COVID-19 period appears to mark a turning point, exerting substantial downward pressure. This trend now seems to be solidifying, indicating that the divergence is structural rather than cyclical.

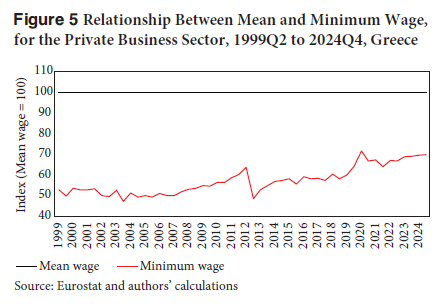

All available data indicate that wage levels in Greece have remained significantly low. Wages have been heavily suppressed, and the gap between the mean and minimum wage in the business sector has narrowed over time. Figure 5 illustrates the long-term relationship between the mean and minimum wage per employee, showing a clear convergence between the two. This trend becomes particularly evident after 2012, following substantial wage cuts. Since then, the minimum wage has not only served as a starting point for newly hired workers but has also become increasingly representative of a broader segment of the workforce. This pattern highlights a growing concentration of workers near the lower end of the wage distribution.

Conclusions

The above analysis suggests that the Greek economy has experienced profound transformations. Internal devaluation and labor market flexibility in Greece have contributed to the suppression of average wages measured in PPS. Greek employees work more hours than those in any other EU27 country, yet their compensation remains comparatively low. To improve working conditions and restore wage adequacy, several policy initiatives should be considered:

- Strengthening collective bargaining is essential for improving industrial relations. Trade unions should be empowered to negotiate better wages and better working conditions.

- Ensuring that the minimum wage provides for a decent standard of living, rather than serving merely as a low-cost entry point to the labor market. An adequate minimum wage supports social progress and helps reduce in-work poverty.

- Raising minimum standards for working time (including limits on working days and weeks, rest periods, and paid annual leave) would help promote a healthier balance between work and personal life.

- Promoting job guarantee schemes (Antonopoulos et al. 2014), which offer employment at wages above the minimum, could serve as a structural solution to overemployment and low pay.

Vlassis Missos and Research Associate Nikolaos Rodousakis are research fellows at the Centre for Planning and Economic Research and can be contacted at [email protected].

References

Antonopoulos, R., S. Adam, K. Kim, T. Masterson, and D. Papadimitriou. 2014. “Responding to the Unemployment Challenge: A Job Guarantee Proposal for Greece.” Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Research Project Report.

Eurostat. 2008. European Price Statistics: An Overview, European Commission.

Missos, V. 2024. “Comparing the average hourly wage between Greece and the EU27.” Greek Economic Outlook 54 (June): 50–53.

Missos, V., C. Domenikos, and N. Pontis. 2024a. “Hardening the EU Core-Periphery Lines 2009–2019: Dependency, Neoliberalism, Welfare Reformation and Poverty in Greece.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 69: 171–82.

Missos, V., P. Blunt, C. Domenikos, and N. Pontis. 2024b. “Inflated Inequality or Unequal Inflation? A Case for Sustained ‘Two-Sided’ Austerity in Greece.” European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies: Intervention 21(3): 396–415,

Papadimitriou, D. B., N. Rodousakis, G. Toshiro Yajima, and G. Zezza. 2022a. “Greece: Recovery, or Another Recession?” Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Strategic Analysis October 2022.

———. 2022b. “Is Greece on the Road to Economic Recovery?” Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Strategic Analysis March 2022.

———. 2024. “Greece: Time to Reduce the Dependence on Imports.” Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Strategic Analysis February 2024.

———. 2025. “Greece: Growing on an Unsustainable Path.” Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Strategic Analysis March 2025.

Pierros, C. 2021. “Assessing the Internal Devaluation Policy Implemented in Greece in an Empirical Stock-Flow Consistent Model.” Metroeconomica 72(4): 905–43.

Vaitsos, C. and V. Missos. 2025. “Institutional Blitzkrieg and Growthless Employment: Aspects of a New Developmental Paradigm for Greece.” Forum for Social Economics.

[i] For the current and future state of the Greek economy, see Papadimitriou et al. (2022a; 2022b; 2024; 2025).

[ii] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/nama_10_fte_esms.htm

[iii] https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jul/01/greece-introduces-growth-oriented-six-day-working-week