The Incoming Recession: Are Imports the Real Culprit?

The preliminary estimates for real GDP growth in the first quarter of 2025 show an annualized contraction rate of 0.28 percent, along with an extraordinary increase in imports of 41.3 percent. Most commentators rushed to indicate that the contraction was due to the rise in imports, as, for instance, with the recent Reuters headline stating “GDP contraction driven by record trade gap due to import surge.” It is true that imports have surged, especially taking advantage of the “de minimis” exemption for Chinese goods that came to an end at midnight on Friday, May 2, 2025. The de minimis exemption allows goods worth $800 or less to come into the United States almost duty-free, without inspections and with very little paperwork. These small shipments under the de minimis exemption accounted for over 1.36 billion shipments in the fiscal year 2024—more than double the number four years earlier, according to the US customs agency. This extraordinary type of imports represents, according to The Guardian, “more than 90% of all the cargo entering the US. About 60% of those packages come from China.”

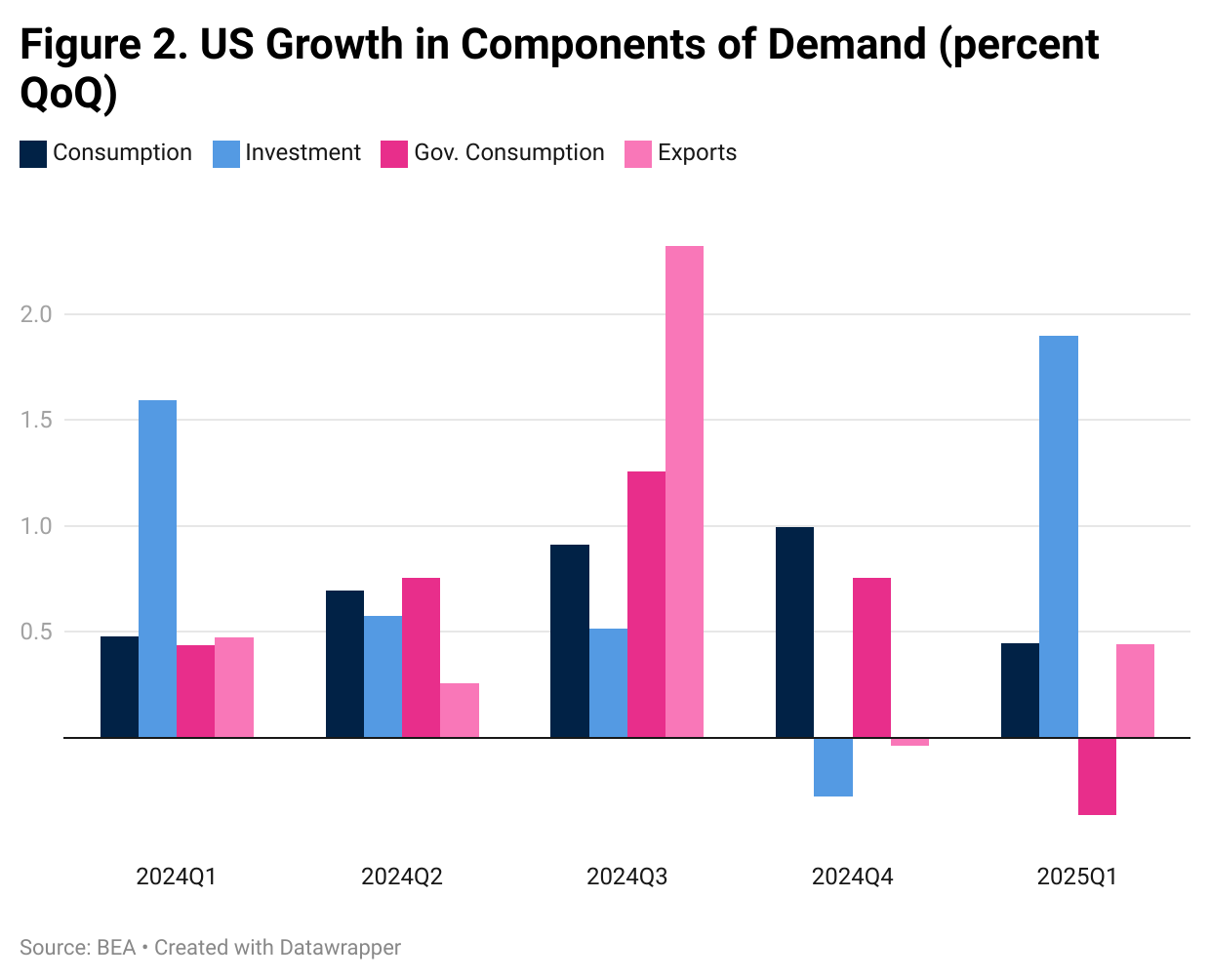

It is well known that the demand components of GDP are comprised of consumption, investment, government expenditure, and exports minus imports. That negative contribution from imports may lead those less knowledgeable of national accounting to assume a direct, one-to-one negative link between imports and GDP. A better informed view falsifies this conclusion, since the value of imported goods also shows up in consumption, investment, and government expenditure, so that an increase in imports has a negative effect on domestic production only when the domestic sector is switching from domestically produced goods to foreign goods, which is not currently the case in the United States.

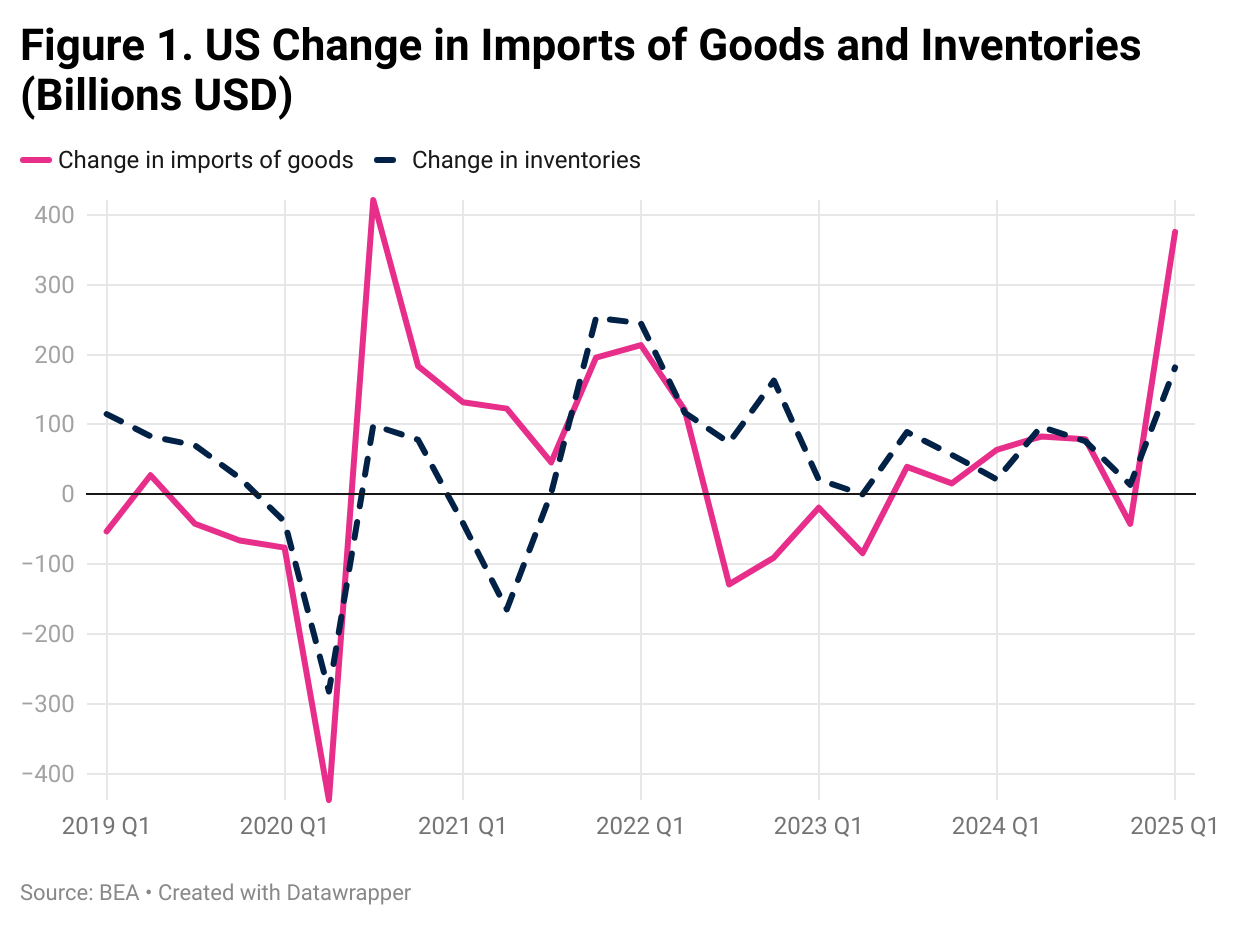

Certainly, the surge in imports is linked to the uncertainty related to the introduction of the Trump tariffs, which, as indicated above, have prompted companies to stockpile foreign products before tariffs become effective. This is corroborated by the link between the change in imports of goods and the change in inventories demonstrated in Figure 1. However, the reason for the (small) drop in real GDP in the first quarter of 2025 should be sought elsewhere.

Commentary on GDP growth usually focuses on annualized growth rates that often exaggerate short-term movements. If we look, for instance, at the annual change in real GDP in 2025Q1, we observe a positive 2 percent growth against the same quarter of the previous year. Reviewing the quarterly growth rate of each of the components of demand, the only one showing a negative sign (Figure 2) is government expenditure, which has fallen by 0.4 percent (1.45 percent at an annualized rate). The culprit for the slowdown in GDP is, therefore, mainly the shock from the federal government’s drop in expenditures—and given the administration’s proposed cuts to non-defense discretionary spending of over $163 billion starting next fiscal year, the coming GDP contraction will ultimately be much steeper.