What Do We Save When We DOGE the Government?

The second Trump administration has seemingly added a new term to the English vocabulary – getting DOGE-ed. Almost every week we hear about another government agency getting the DOGE treatment, i.e., firing personnel, closing down offices, etc. The Department of Government Efficiency is supposedly making our government more efficient and hence saving the taxpayers some money. But what does it mean for the government to save money? And do we really save the population anything when we cut government spending?

In this policy note we explain that analyzing the government as if it’s a household or a firm leads to inaccurate conclusions regarding “saving” and “efficiency.” Moreover, the current discourse around waste muddles different definitions of efficiency to advance the political goal of shrinking the federal government, and obscures the fundamentally value-laden nature of our policy choices.

The Forest vs. the Trees

[1] In any principles of economics class students learn that the macro logic, where we look at the forest, is different from the micro logic where we study the trees. Microeconomics, for instance, focuses on the behavior of the representative firm and the household independently. In macroeconomics, however, what happens in one sector, such as the government, has repercussions for others, such as the private sector.

John Maynard Keynes, the father of Macroeconomics was the first to recognize that the whole of the economy was greater than the sum of its parts. The famous example he used was the so-called paradox of thrift. Suppose an individual household decides to ramp up its saving. It can do so by cutting its consumption – buying fewer avocado toasts and lattes! But can the society as a whole save more by consuming less? Not necessarily, because someone’s consumption spending is income for someone else in the economy. If consumers spend less there will be less national income. Less national income, in turn, means less saving for the economy as a whole. Therein lies the paradox — while an individual (or a household) can save more by consuming less, the economy as a whole will end up with less saving if it cuts its consumption spending.

This macroeconomic logic can be used to understand what happens when the government decides to spend less, whether by DOGE-ing different agencies or by cutting programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicare. If the government is spending less, someone, such as government employees who were laid off, is earning less income. Since people’s consumption depends largely on their income, the newly unemployed government workers will cut their own spending (and saving). Whoever was receiving their spending as income now receives less of it and will consequently cut their own consumption spending (and saving). This cycle continues with the initial cut in government spending multiplied into a larger decrease in national income. Reducing government spending in the name of saving money actually leads to less saving in the private sector as it lowers our national income. Thinking about government “saving” in the same way we think about saving as individuals ignores the repercussions that spending cuts in one sector have for others. It muddles the forest for the trees.

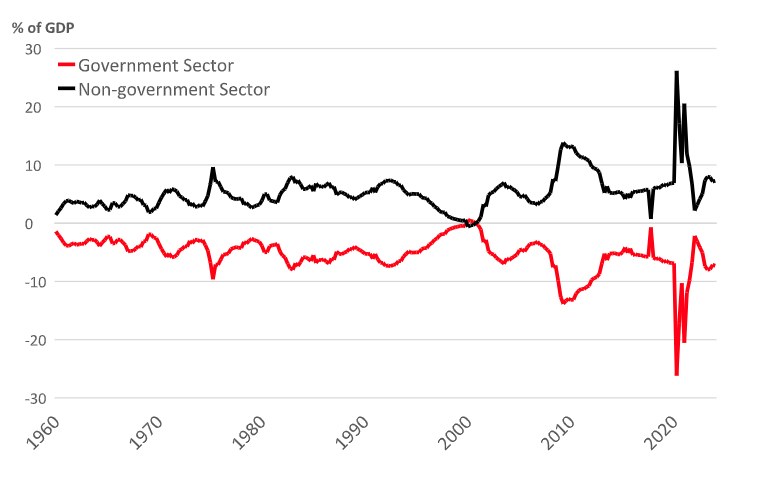

To further illustrate that DOGE-ing the government doesn’t really “save” us anything in financial terms we can look at sectoral balances – the combination of financial balances of the various sectors of the economy. Since someone’s income is someone’s expenditure, at the level of the economy as a whole income equals expenditure. If we divide the economy into the government and non-government sectors, we can see that if one sector of the economy has a positive financial balance (it’s earning more than its spending) then the other sector has to have a negative financial balance (it’s earning less than its spending).

In other words, a government deficit is always matched by a surplus in the non-government sector, as shown in Figure 1, while a government surplus necessarily means a deficit for the non-government sector. This is not a theory; it’s accounting. While conventional wisdom views government surpluses as adding to national saving, they actually lead to deficits for the non-government sector, including firms and households.

Figure 1. U.S. Sectoral Balances, Percent of GDP 1960-2024

A good example of understanding the relationship between different sectors is the “Clinton surpluses”, the last time the federal government budget was in a surplus. While at the time the budget surplus was extolled as evidence of good economic management, in reality the non-government sector was financing this surplus by running a deficit (and accumulating debt). The private sector deficits were unsustainable, as Levy Institute scholars noted at the time (Godley and Wray, 1999). They ultimately culminated in the global financial crisis a few years later.

Can Government Save “Money”?

Even if one recognizes the macroeconomic effects of cutting government spending explained in the previous section, they may still argue that the US government has been living beyond its means by running deficits and accumulating debt. Indeed, reducing the national debt is one of the purported goals of the administration, and calls to do so are likely to intensify given the recent downgrade of the U.S. credit rating by Moody’s[2]. But as many scholars associated with the Levy Institute have explained over the years, sovereign governments do not have to fear deficits and debt (Wray 2015; 2022). As issuers of their own currency, they can neither run out of that currency nor save it. Money is merely the government’s liability which it emits in the process of spending and eliminates as taxes are paid, returning those liabilities back to the issuer, the government.

Can Government Spending be Wasteful?

But even as government spending creates income and saving for the non-government sector, can that spending still be wasteful? To answer this question, it’s important to clarify the definition of the term “waste.”

At least two senses of the word are relevant: 1) government spending is “wasteful,” if it’s spent on something society doesn’t want (allocative efficiency) or 2), government spending is “wasteful,” if it means using more resources than necessary to deliver the public goods (productive efficiency).

Allocative Efficiency

The first sense is on display in many recent policy debates. For example, some believe foreign assistance is “wasteful” simply because they don’t consider it a national priority. Others may feel the same way about sheltering newly arrived immigrants awaiting asylum cases. Still others may believe it’s unnecessary to devote added spending to cancer research, to protect consumers from fraud in the financial industry, or to ensure healthcare for the poor.

These are ultimately value judgments. As such, they should be decided through our political processes, involving both the legislative and executive branches. No set of economic facts can dictate to us our collective value judgments.

Productive Efficiency

The second sense – using more resources than necessary to get what we want – appears more value-neutral. Economists refer to this as “productive inefficiency.” For example, it may be possible to have increased health care for the poor without giving up anything else, if we can find a way to produce these healthcare services with fewer resources.

Much of the current discourse over government “waste” suffers from a conflation between these two senses of “waste” – the first in the sense of spending money on things we do not want, and the second in the sense of unnecessary spending on what we do want.

Consider Medicaid. The purpose of Medicaid is to provide healthcare for the indigent and the disabled. The House of Representatives recently passed a bill[3] directing the Energy and Commerce Committee to cut $880 billion in 10 years. Since it is unlikely that they can do so without significantly reducing Medicaid benefits[4], cuts of this magnitude represent a judgment that it is the goal itself that is wasteful, not the means by which it is achieved.

Now consider the case of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Since its inception in 2011, it has secured over $21 billion in consumer relief[5] from its enforcement of rules and regulations in the financial industry. However, reports indicate that the Trump administration plans to lay off nearly all CFPB employees. Just after Trump’s election, Elon Musk (who initially headed up DOGE, although is now reportedly stepping back) tweeted, “Delete CFPB. There are too many duplicative regulatory agencies.” The second sentence suggests that we should “delete” the CFPB because the same services could be achieved with less labor – in other words, with fewer resources.

But, as this administration has made clear, “deleting” the CFPB is not about delivering the same services with fewer resources; it’s about drastically reducing them. Already, the CFPB has announced that it is dropping its lawsuit against Capital One[6] for misleading consumers about high-interest savings accounts, a major credit reporting agency[7] for deceptive marketing practices, and several others[8]. In this administration’s opinion, protecting consumers from deceptive practices of financial institutions is simply not “valuable” enough, and therefore, “waste.”

Even if we were to interpret the Trump administration’s actions of trying to deliver the same government services with fewer resources as an attempt to “save” real resources, this only benefits us if those resources are actually used in some other way. As Adam Smith (2016 [1776]) explained centuries ago, real wealth is the goods and services we produce, not the money needed to buy them. Thus, the mere act of spending less money on resources doesn’t save us anything unless those resources are used to produce something else. If government workers lose their jobs nothing is gained unless the labor they provide can be used for producing other goods or services.

The question of what counts as “waste” raises yet another important issue. Even if we were to stay focused on the efficient use of resources, and leave value-judgments to the political process (where it belongs), it’s reasonable to ask whether we should think of labor as a mere “resource” in the first place (as economists typically do). Put otherwise, the very decision to think of labor this way might itself reflect a kind of value-judgment – one that views labor primarily as a means to an end. We could just as well decide that the provision of meaningful work at a living wage is itself a legitimate end. The changing needs and wants of society does not necessarily mean that human labor should be treated as nothing more than disposable commodities in the private market. (To note just one alternative, the government could institute a Federal Job Guarantee[9] that absorbs unemployed labor when there is slack in the market.)

As the recent government funding cuts highlight, the question of whether a person is properly deemed “waste” (including not just government employees, but private farmers[10] and workers who lost illegally frozen funds[11]) can be a matter of debate. While we would all like to have “more” with “less,” the question of what exactly we want more of – including work with dignity – remains a political and value-based judgment, not a merely “economic” one.

Lastly, we could argue that the US government has indeed become inefficient in the productive sense in the past few decades. But it’s not because of the inefficiency of bureaucrats, but rather because it relies on the private sector for almost every service it delivers.[12] This “contracting out” of government services is the reason why the American government is paying more money for fewer real resources as a multitude of middle people take their cut. To the extent that the department of government efficiency is trying to supercharge the privatization of the American government, it will make things less, not more efficient.

Conclusion

Our political debates around government saving, waste and efficiency remain superficial. We should clearly distinguish between saving money, which is not possible for the issuer of the currency, such as the government, vs. saving resources, which are scarce at any given time. Similarly, we should differentiate between spending money on resources to produce what we want, and getting what we want with fewer resources. The former concerns value judgments that are to be hashed out in our political processes (and, when needed, funded by Congress in a budget — which the executive branch cannot lawfully ignore or contravene, whether through DOGE, executive orders, or any other mechanism.) The latter is more value-neutral – but even there, we need to avoid falling into the trap of thinking that spending less money on resources means that we are saving more. If those resources remain idle, then we potentially produce less, and, the country as a whole ends up worse off.

Mark Silverman is assistant professor of economics at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa.

Research Scholar Yeva Nersisyan is chair and associate professor of economics at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa.

References

Godley, W. and L. R. Wray. 1999. “Can Goldilocks Survive?”, Policy Note 1999/4, The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

Smith, A. 2016 [1776]. The wealth of nations. Aegitas.

Wray, L. R. 2022. Making money work for us: how MMT can save America. John Wiley & Sons.

Wray, L. R. 2015. Modern money theory: A primer on macroeconomics for sovereign monetary systems. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[1] A portion of Section 2 has been published as an op-ed in The Pittsburg Post-Gazette, available at: LINK

[4] Burns, A. “The Math is Conclusive: Major Medicaid Cuts Are the Only Way to Meet House Budget Resolution Requirements”, KFF, March 7, 2025. Available at: LINK

[5] Americans for Financial Reform, “Fact Sheet: AFREF Coalition Fact Sheet on CFPB Protecting People and Families,” Jan 21, 2025. Available at: LINK

[6] Wamsley, L. “The CFPB drops its lawsuit against Capital One, marking a major reversal”, NPR, February 27, 2025. Available at: LINK

[7] Dhaliwal, A.J. S., Madia, M. N., Zhang, B. “CFPB Drops Two More Major Lawsuits,” The National Law Review Consumer Finance and Fintech Blog, March 14, 2025. Available at: LINK

[8] Chapman, M. “CFPB drops lawsuit against Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo over Zelle fraud,” The Associated Press, March 5, 2025. Available at: LINK

[10] Knappenberger, R. “Farmers sue Trump administration to unfreeze USDA grants”, Courthousenews.com., March 13, 2025. Available at: LINK

[11] Lavin, N. “R.I. federal judge orders Trump administration to resume grant payments to environmental nonprofits”, Rhode Island Current, April 16, 2025. Available at: LINK

[12] Grabar, H. “Consultants Gone Wild”, Slate, Feb. 3, 2023. Available at: LINK